The Future of Leadership Development

The need for leadership development has never been more urgent. Companies of all sorts realize that to survive in today’s volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous environment, they need leadership skills and organizational capabilities different from those that helped them succeed in the past. There is also a growing recognition that leadership development should not be restricted to the few who are in or close to the C-suite. With the proliferation of collaborative problem-solving platforms and digital “adhocracies” that emphasize individual initiative, employees across the board are increasingly expected to make consequential decisions that align with corporate strategy and culture. It’s important, therefore, that they be equipped with the relevant technical, relational, and communication skills.

The leadership development industry, however, is in a state of upheaval. The number of players offering courses to impart the hard and soft skills required of corporate managers has soared. And yet organizations that collectively spend billions of dollars annually to train current and future executives are growing frustrated with the results. Several large-scale industry studies, along with our own in-depth interviews with clients, indicate that more than 50% of senior leaders believe that their talent development efforts don’t adequately build critical skills and organizational capabilities.

The Problems with Traditional Executive Education

Chief learning officers find that traditional programs no longer adequately prepare executives for the challenges they face today and those they will face tomorrow. Companies are seeking the communicative, interpretive, affective, and perceptual skills needed to lead coherent, proactive collaboration. But most executive education programs—designed as extensions of or substitutes for MBA programs—focus on discipline-based skill sets, such as strategy development and financial analysis, and seriously underplay important relational, communication, and affective skills.

No wonder CLOs say they’re having trouble justifying their annual training budgets.

Executive education programs also fall short of their own stated objective. “Lifelong learning” has been a buzzword in corporate and university circles for decades, but it is still far from a reality. Traditional executive education is simply too episodic, exclusive, and expensive to achieve that goal. Not surprisingly, top business schools, including Rotman and HBS, have seen demand increase significantly for customized, cohort-based programs that address companies’ idiosyncratic talent-development needs. Corporate universities and the personal learning cloud—the growing mix of online courses, social and interactive platforms, and learning tools from both traditional institutions and upstarts—are filling the gap.

There are three main reasons for the disjointed state of leadership development. The first is a gap in motivations. Organizations invest in executive development for their own long-term good, but individuals participate in order to enhance their skills and advance their careers, and they don’t necessarily remain with the employers who’ve paid for their training. The second is the gap between the skills that executive development programs build and those that firms require—particularly the interpersonal skills essential to thriving in today’s flat, networked, increasingly collaborative organizations. Traditional providers bring deep expertise in teaching cognitive skills and measuring their development, but they are far less experienced in teaching people how to communicate and work with one another effectively. The third reason is the skills transfer gap. Simply put, few executives seem to take what they learn in the classroom and apply it to their jobs—and the farther removed the locus of learning is from the locus of application, the larger this gap becomes. To develop essential leadership and managerial talent, organizations must bridge these three gaps.

The Skills Transfer Gap: What Is Learned Is Rarely Applied

One of the biggest complaints we hear about executive education is that the skills and capabilities developed don’t get applied on the job. This challenges the very foundation of executive education, but it is not surprising. Research by cognitive, educational, and applied psychologists dating back a century, along with more-recent work in the neuroscience of learning, reveals that the distance between where a skill is learned (the locus of acquisition) and where it is applied (the locus of application) greatly influences the probability that a student will put that skill into practice.

Indeed, it’s much easier to use a new skill if the locus of acquisition is similar to the locus of application. This is called near transfer. For instance, learning to map the aluminum industry as a value-linked activity chain transfers more easily to an analysis of the steel business (near transfer) than to an analysis of the semiconductor industry (far transfer) or the strategy consulting industry (farther transfer).

To be sure, when we say “distance,” we’re not referring just to physical range. New skills are less likely to be applied not only when the locus of application is far from the locus of acquisition in time and space (as when learning in an MBA classroom and applying the skills years later on the job) but also when the social (Who else is involved?) and functional (What are we using the skill for?) contexts differ.

Anecdotal evidence on skills transfer suggests that barely 10% of the $200 billion annual outlay for corporate training and development in the United States delivers concrete results. That’s a staggering amount of waste. More to the point, it heightens the urgency for the corporate training and executive development industries to redesign their learning experiences.

The good news is that the growing assortment of online courses, social and interactive platforms, and learning tools from both traditional institutions and upstarts—which make up what we call the “personal learning cloud” (PLC)—offers a solution. Organizations can select components from the PLC and tailor them to the needs and behaviors of individuals and teams. The PLC is flexible and immediately accessible, and it enables employees to pick up skills in the context in which they must be used. In effect, it’s a 21st-century form of on-the-job learning.

In this article we describe the evolution of leadership development, the dynamics behind the changes, and ways to manage the emerging PLC for the good of both the firm and the individual.

The State of Leadership Development

The traditional players in the leadership development industry—business schools, corporate universities, and specialized training companies and consultancies—have been joined by a host of newcomers. These include human resource advisory firms, large management consultancies such as McKinsey and BCG, and digital start-ups such as Coursera and Udacity. This is a rapidly shifting landscape of service providers, but it’s a world we’ve gotten to know intimately as educators, advisers, and leaders of the executive education programs at Rotman (in Mihnea’s case) and Harvard Business School (in Das’s case). And to help make sense of it all, we’ve constructed a table that compares the players (see below).

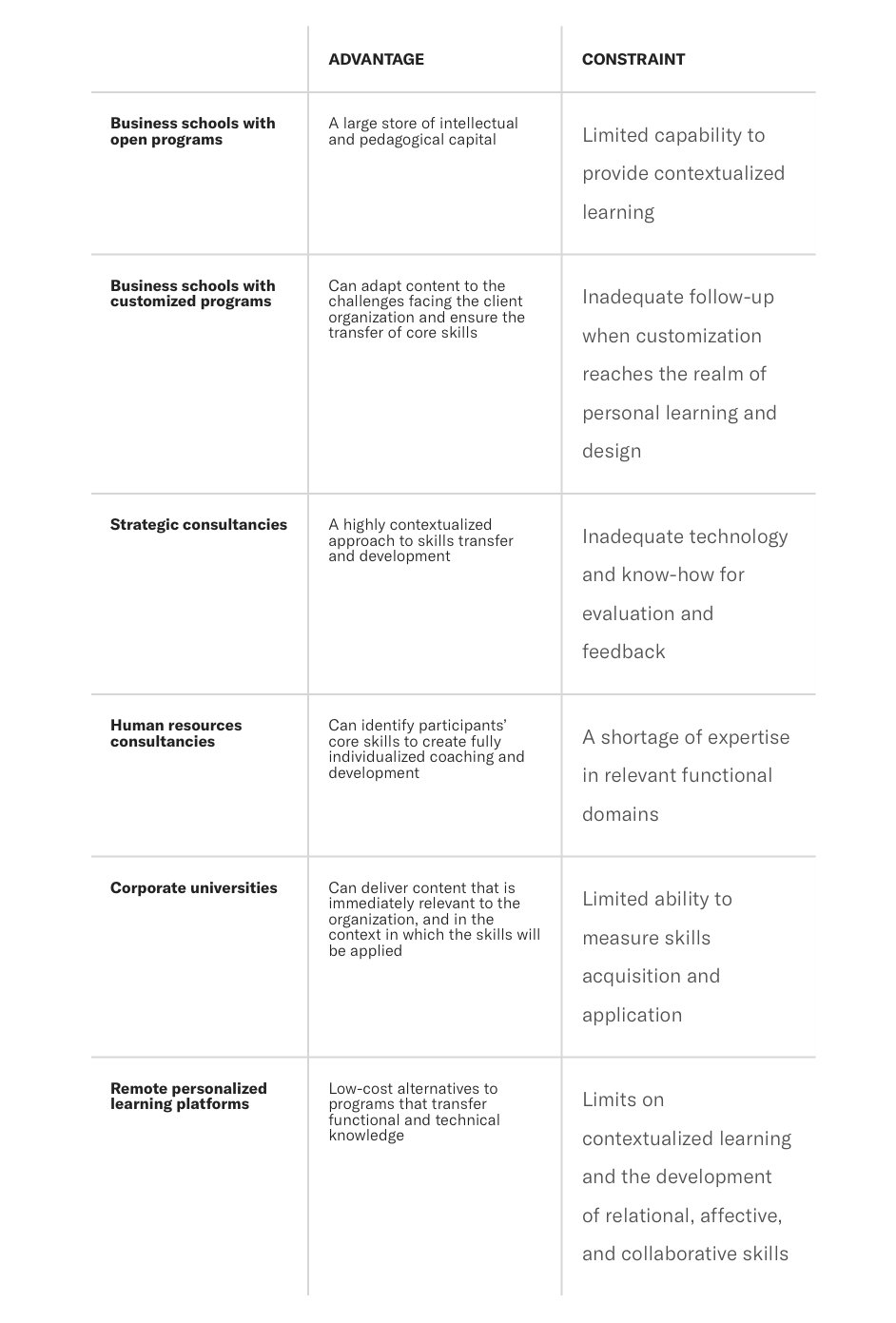

The Landscape of Providers

As demand grows for executive education that is customizable, trackable, and measurably effective, new competitors are emerging. Business schools, consultancies, corporate universities, and digital platforms are all vying to provide skills development programs, and each player has certain advantages and constraints.

We’re now seeing powerful trends reshaping the industry and fueling the emergence of the PLC as a networked learning infrastructure. First, the PLC has lowered the marginal cost of setting up an in-house learning environment and has enabled chief human resources officers (CHROs) and chief learning officers (CLOs) to make more-discerning decisions about the right experiences for the people and teams in their organizations. A Unicon study reports that the number of corporate universities—which provide education in-house, on demand, and, often, on the job—has exploded to more than 4,000 in the United States and more than twice that number worldwide. We believe that in the future, however, even as firms offer learning opportunities to more leaders throughout their organizations, the shifting cost structure resulting from the digitization of learning environments will lead to only a modest increase in resources devoted to leadership development.

The second trend is the decline of standard classroom-based programs for executive development, such as those primarily offered by business schools and universities. Most organizations are demanding pre- and postmeasures of the acquisition and application of relevant skills—such as communicative competence and leadership acumen—that traditional programs were never designed to deliver.

The third trend is the rise of customizable learning environments, through platforms and applications that personalize content according to learners’ roles and their organizations’ needs. The dominant platforms now count millions of enrollees in individual courses and tens of millions of total users.

These trends are linked and form a cohesive pattern: As learning becomes personalized, socialized, and adaptive, and as organizations get more sophisticated at gauging the return on investment in talent development, the industry is moving away from prepackaged one-size-fits-all material and turning instead to the PLC. The PLC enables the fast, low-cost creation of corporate universities and in-house learning programs in the same way that platforms such as Facebook and Instagram facilitate the formation of discussion groups. It is the “petri dish” that fosters the rapid growth of learning communities. And it’s vital to keeping managers engaged and growing on the job.

Underlying and amplifying these trends is the rapid digitization of content and interaction, which is reshaping the leadership development industry in three important ways. First, it allows the disaggregation (or unbundling) of the low-cost elements of a program from the high-cost ones. Education providers’ profits depend on their ability to bundle low-cost content—lectures, case discussions, exercises, and the like—with high-value experiences such as personalized coaching, project-based learning, and feedback-intensive group sessions. The more high-touch services included in the package, the more a provider can charge.

Second, digitization makes it easier to deliver value more efficiently. For example, classroom lectures can be videotaped and then viewed online by greater numbers of learners at their convenience. Similarly, discussion groups and forums to deepen understanding of the lecture concepts can be orchestrated online, often via platforms such as Zoom, Skype, and Google Hangouts, allowing many more people to participate—and with less trouble and expense. Millennials are already comfortable with social media–based interactions, so the value of being physically present on campus may be wearing thin anyway. And because discrete components of an online education program—individual lectures, case studies, and so forth—can be priced and sold independently, the cost of developing various skills has dropped—particularly technical and analytical skills whose teaching and learning have become sufficiently routinized.

Finally, digitization is leading to disintermediation. Traditionally, universities, business schools, and management consultancies have served as intermediaries linking companies and their employees to educators—academics, consultants, and coaches. Now, however, companies can go online to identify (and often curate) the highest-quality individual teachers, learning experiences, and modules—not just the highest-quality programs. Meanwhile, instructors can act as “free agents” and take up the best-paying or most-satisfying teaching gigs, escaping the routines and wage constraints of their parent organizations.

The Rise of the Personal Learning Cloud

The PLC has been taking shape for about a decade. Its components include MOOCs (massive open online courses) and platforms such as Coursera, edX, and 2U for delivering interactive content online; corporate training and development ecosystems from LinkedIn Learning, Skillsoft, Degreed, and Salesforce Trailhead, targeting quick, certifiable mastery of core skills in interactive environments; on-demand, solution-centric approaches to leadership development from the likes of McKinsey Solutions, McKinsey Academy, BCG Enablement, and DigitalBCG; and talent management platforms such as SmashFly, Yello, and Phenom People, which make it possible to connect learning needs and learner outcomes to recruitment, retention, and promotion decisions.

The PLC has four important characteristics:

1. Learning is personalized.

Employees can pursue the skills development program or practice that is right for them, at their own pace, using media that are optimally suited to their particular learning style and work environment. The PLC also enables organizations to track learner behaviors and outcomes and to commission the development and deployment of modules and content on thefly to match the evolving needs of individuals and teams.

2. Learning is socialized.

As the experiences of Harvard’s HBX and McKinsey’s Academy series have shown, learning happens best when learners collaborate and help one another. Knowledge—both “know-what” and “know-how”—is social in nature. It is distributed within and among groups of people who are using it to solve problems together. The PLC enables the organic and planned formation of teams and cohorts of learners who are jointly involved in developing new skills and capabilities.

3. Learning is contextualized.

As our interviews revealed, and as recent evidence from LinkedIn Learning has shown, most executives value the opportunity to get professional development on the job, in ways that are directly relevant to their work environment. The PLC enables people to do this, allowing them to learn in a workplace setting and helping ensure that they actually apply the knowledge and skills they pick up.

4. Learning outcomes can be transparently tracked and (in some cases) authenticated.

The rise of the PLC does not imply the demise of credentialing or an end to the signaling value of degrees, diplomas, and certificates. Quite the contrary: It drives a new era of skills- and capabilities-based certification that stands to completely unbundle the professional degree. Indeed, in more and more cases, it’s no longer necessary to spend the time and money to complete a professional degree, because organizations have embraced certifications and microcertifications that attest to training in specific skills. And seamless, always-on authentication is quickly becoming reality with the emergence of blockchains and distributed ledgers—such as those of Block.io and Learning Machine. Microcredentials are thus proliferating, because the PLC enables secure, trackable, and auditable verification of enrollment and achievement.

The PLC makes it possible for CLOs and CHROs to be precise both about the skills they wish to cultivate and about the education programs, instructors, and learning experiences they want to use. The PLC’s expanding ecosystem covers a broad array of skills. At one end lie functional skills (such as financial-statement analysis and big-data analytics) that involve cognitive thinking (reasoning, calculating) and algorithmic practices (do this first, this next). The PLC is already adept at helping individuals learn such skills at their own pace, and in ways that match the problems they face on the job.

At the other end of the spectrum lie skills that are difficult to teach, measure, or even articulate; they have significant affective components and are largely nonalgorithmic. These skills include leading, communicating, relating, and energizing groups. Mastery depends on practice and feedback, and the PLC is getting steadily better at matching talented coaches and development experts with the individuals and teams that need such training.

But this is just the beginning. The PLC is proving to be an effective answer to the skills transfer gap that makes it so difficult to acquire communicative and relational proficiencies in traditional executive education settings. Meaningful, lasting behavioral change is a complex process, requiring timely personalized guidance. Start-ups such as SHIFT and Butterfly Coaching & Training are providing executive teams with a fabric of interactive activities that emphasize mutual feedback and allow them to learn on the job while doing the work they always do. BCG’s Amethyst platform allows both executives and teams to enter into developmental relationships with enablers and facilitators so that they can build the collaborative capital they and their organizations need.

The ubiquity of online training material allows CLOs to make choices among components of executive education at levels of granularity that have simply not been possible until now. They can purchase only the experiences that are most valuable to them—usually at a lower cost than they would pay for bundled alternatives—from a plethora of providers, including coaches, consultants, and the anywhere, anytime offerings of the PLC. And executives are able to acquire experiences that fulfill focused objectives—such as developing new networks—from institutions such as Singularity University and the Kauffman Founders School, which are specifically designed for the purpose.

For learners, the PLC is not just an interactive learning cloud but also a distributed microcertification cloud. Blockchain-trackable microdegrees that are awarded for skill-specific (rather than topic-specific) coursework allow individuals to signal credibly (that is, unfakeably) to both their organizations and the market that they are competent in a skill. In addition, the PLC addresses the motivations gap by allowing both organizations and executives to see what they’re buying and to pay for only what they need, when they need it.

Finally, the PLC is dramatically reducing the costs of executive development. Traditional programs are expensive. Courses take an average of five days to complete, and organizations typically spend between $1,500 and $5,000 per participant per day. These figures do not include the costs of selecting participants or measuring how well they apply their newly acquired skills and how well those skills coalesce into organizational capabilities. Nor do the figures account for the losses incurred should participants choose to parlay their fresh credentials and social capital into employment elsewhere. Assuming, conservatively, that these pre- and posttraining costs can amount to about 30% of the cost of the programs, externally provided executive development can cost a company $1 million to $10 million a year, depending on the industry, the organizational culture and structure, and the nature of the programs in which the enterprise invests.

By contrast, the PLC can provide skills training to any individual at any time for a few hundred dollars a year. Furthermore, these cloud services allow organizations to match cost to value; offer client-relation management tools that can include preassessment and tracking of managerial performance; and deliver specific functional skills from high-profile providers on demand via dedicated, high-visibility, high-reliability platforms. Thus a 10,000-person organization could give half its employees an intensive, year-round program of skills development via an internally created and maintained cloud-based learning fabric for a fraction of what it currently pays to incumbent providers for equivalent programs.

What the Future Holds

For companies that tap into the PLC, the fixed costs of talent development will become variable costs with measurable benefits. Massively distributed knowledge bases of content and learning techniques will ensure low marginal costs per learner, as learning becomes adaptive. The ability to clearly specify the skill sets in which to invest, and the ability to measure the enhancement of individuals’ learning and firms’ capabilities, will ensure that the (variable) cost base of a corporate university can be optimized to suit the organization and adapted as necessary.

Individual learners will benefit from a larger array of more-targeted offerings than the current ecosystem of degrees and diplomas affords, with the ability to credibly signal skills acquisition and skills transfer in a secure distributed-computing environment. People will be able to map out personalized learning journeys that heed both the needs of their organizations and their own developmental and career-related needs and interests. And as the PLC reduces the marginal and opportunity costs of learning a key skill and simultaneously makes it easier to demonstrate proficiency, far more people will find it affordable and worthwhile to invest in professional development.

Meanwhile, with CLOs having greater visibility into the skillsdevelopment blueprints that providers use, the signaling value of traditional providers’ offerings will decline because their programs will become easily replicable. That’s already evident from the increasing number of “bake-offs” in which the leading B-schools are having to participate to win corporate business. Recently a prominent global financial-services firm considered training proposals from no fewer than 10 top-tier schools in the final round of evaluation—reflecting competition in the market that would not have happened even five years ago.

Increased competition will force incumbents to focus on their comparative advantage, and they must be mindful of how this advantage evolves as the PLC gains sophistication. We already see that the disaggregation of content and the rise of “free agent” instructors has made it possible for new entrants to work directly with name-brand professors, thus diminishing the value that many executive education programs have traditionally provided.

Now the PLC is starting to cut into the domain of higher-touch classroom-type experiences, with live case teaching and “action learning” programs that involve web-based case discussions and customized opportunities to tackle real-life problems. These advances are made possible by the capacity of online learning environments to offer synchronous multiperson sessions and to monitor participants via eye-tracking and gaze-following technologies. For example, IE Business School, in Madrid, uses technology that tracks facial expressions to measure the engagement of learners and facilitators in its online executive education programs. The Rotman School of Management’s Self-Development Lab uses an emotional spectroscopy tool that registers people’s voices, faces, and gazes as they converse.

Business schools will need to significantly rethink and redesign their current offerings to match their particular capabilities for creating teachable and learnable content and for tracking user-specific learning outcomes. They need to establish themselves as competent curators and designers of reusable content and learning experiences in a market in which organizations will need guidance on the best ways of developing and testing for new skills. Given the high marginal and opportunity costs of on-campus education, business schools should reconfigure their offerings toward blended and customized programs that leverage the classroom only when necessary.

Meanwhile, newcomers in leadership development are benefiting significantly from the distributed nature of the PLC—cherry-picking content, modules, and instructors from across the industry to put together the most compelling offerings for their client organizations. Large consultancies such as McKinsey and BCG can tap into their deep knowledge of organizational tasks, activities, and capabilities to provide clients with a new generation of flexible learning experiences, alongside their traditional strategic, organizational, operational, and financial “solution blueprints.” Other entrants—such as human resources consultancies—can lean on their privileged access to organizational talent data (selection metrics and the traits of the most sought-after applicants) to design PLC-enabled “personal development journeys” for new hires, guided by best practices for building skills and tracking learning outcomes.

For individual learners, acquiring new knowledge and putting it into practice in the workplace entails significant behavioral change—something the skills transfer gap tells us is very hard and costly to accomplish through such purely didactic methods as lectures, quizzes, and exams. However, PLC applications that measure, track, and shape user behavior are a powerful way to make prescriptions and proscriptions actionable every day.

In the past, it was hard for the traditional players in leadership development to provide an ROI on the various individual components of their bundled programs. But the PLC is making it possible to measure skills acquisition and skills transfer at the participant, team, and organizational levels—on a per-program, per-session, per-interaction basis. That will create a new micro-optimization paradigm in leadership education—one that makes learning and doing less distinct. The payoff will be significant, for if a new concept, model, or method is to make a difference to an organization, it must be used by its executives, not just understood intellectually. And as platforms change the nature of talent development, leaders will emerge with the skills—and enough real-world practice applying them—to do the right thing, at the right time, for the right reason, in the right way.